Ephemera: Digital and Physical

On writing and reading digital text in a physical world.

I’m a pretty early tech adopter who is conflicted about my strong sentimental attraction for physical text. I gave up writing longhand as soon as I could type decades ago, and I do 90% of my reading and writing on a screen, but there is still something deep about the paper objects associated with writing and reading.

I’ve lately been going to the local library every couple of weeks to print hard copies of poems that I share on a “Poetry Post” in our front yard. As I wait for the printer at the library, I look at the stacks of the local dailies sitting on a table near the printer. I’ll grab one, sit down and return to those halcyon days of holding a newspaper paper in front of me, scanning the pages for interesting headlines and photos, flipping to the jump to finish a good story.

Holding a newspaper or magazine while drinking a cup of coffee is a physical experience that’s deeply embedded. I can recall that posture and those gestures – how to fold it back on itself, or in half – from every phase of my life; it’s probably like a person who prayed ritually every day long enough that it became a part of their body’s muscle memory. If that routine goes away for whatever reason, it’s still there to be reimbodied when the opportunity reenact it arises.

I subscribe to four “legacy” publications in their digital format and read them every day: The San Francisco Chronicle, the New York Times, the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books. Plus there are many other digital readings via Substack and other sources, of course.

Three months ago, when we returned from living in Korea and were setting up our house again, we gave away the last two shelves of our books. When we went to the best used book store in our area, they said they couldn’t take any hardbound fiction, which was pretty much all we had in the nine boxes of books we now had packed in our car. We gave them to the various libraries in the area. I didn’t mind getting no money for them, but I do miss their presence as a part of our home’s aesthetic. People have used books as decorative objects for centuries; realtors use them when they stage a house full of 21st century upgrades, though often they are fake books, like the fake fruit in a bowl.

At this point in the evolution of digital text, I think the experience of reading is objectively better on a digital device than in a paper format. I read novels and book-length non-fiction on my tablet routinely. While reading Paris in Ruins: Love, War and the Birth of Impressionism I was easily able to switch back to the book’s color images or to go online to other sources to look up additional information about random curiosities raised by the text..

The New York Times (for better and worse) has dominated the digital news space because their platform is great– an easily navigable site for text, image, audio and video. They feature “The Long Read” because people do read long pieces. I read much more of the New Yorker’s famously long articles because I always have it with me and can pull it out when I’m sitting on a park bench. I was never a person who put a book or magazines in a backpack should I happen to have a moment to read.

I recently spent time in two famous local bookstores, Kepler’s in Menlo Park and Powell’s in Portland. The shelves and books and Post-It notes with staff recommendations brought on a wave of nostalgia, as my bookstore visiting has gone from biweekly to biannually at best.

I remember going to Kepler’s at its original location as a kid with my dad in the 1960s when it was a hotbed of left politics. Over the decades up till about 2015, with our annual purchases running to many hundreds of dollars, my wife and I would take our reading list to buy the stack for our upcoming summer travels, negotiating who would read what, in what order, so we could minimize the weight in our suitcases.

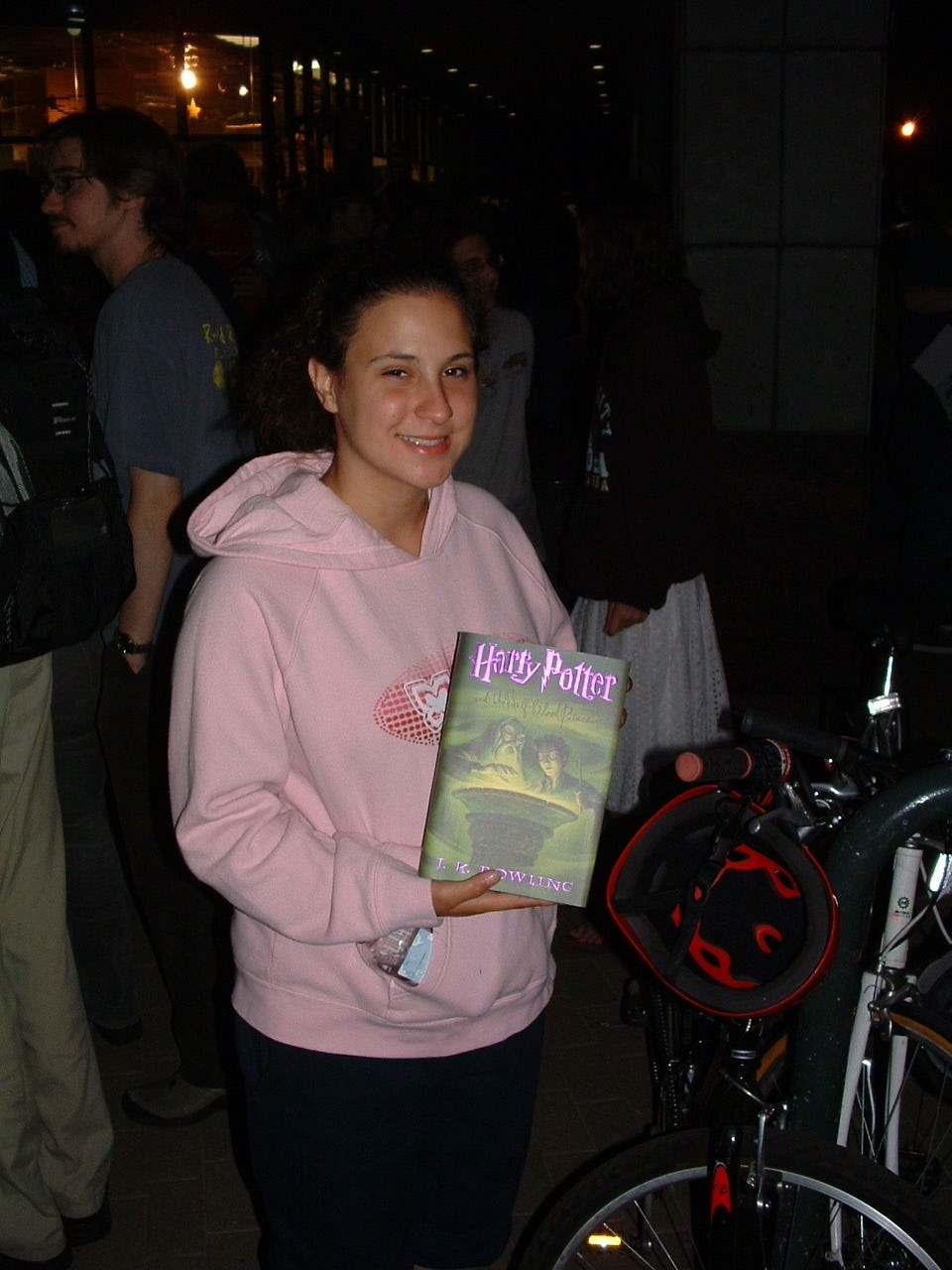

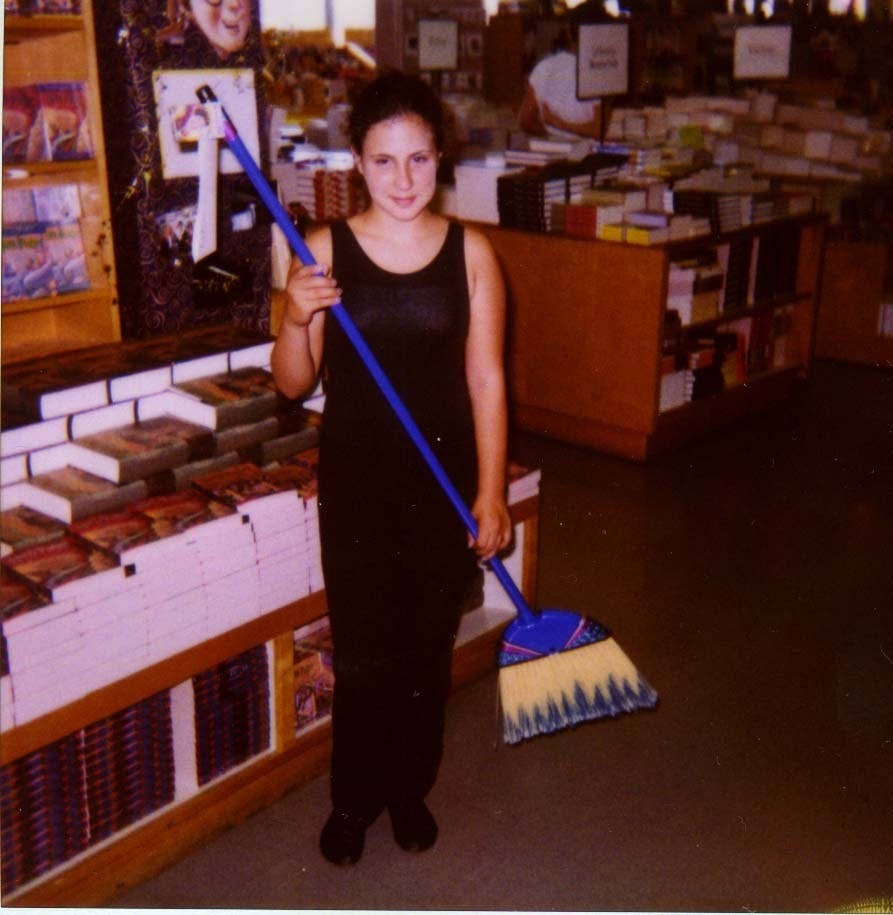

Among my best dad memories are the midnight release parties at Kepler’s for the next Harry Potter book with my daughters and their friends. My elder daughter won an essay contest from Kepler’s about one of the books. The prize was a homemade Nimbus 2000.

I can’t imagine reading a children’s book to my grandchildren off of a screen, though maybe someday the technology will make the experience comparable enough. I think, in the end, it’s about the object itself, not the reading experience, per se. We have a couple of copies of books that I had as a child. I have one inscribed to my brother, from my grandmother, published in the Soviet Union, that he received shortly before he died.

When we boxed up the last sets of books to donate, I kept the ones written by Carson McCullers, Dorothy Richardson and Reynolds Price for purely sentimental reasons. Most will never be read again. I still like seeing them there on the shelf, though. There’s my grandfather’s Yiddish/English dictionary, a shelf of poetry and another shelf of art books inherited from my parents that I rarely open.

For whatever reason of cultural/political upbringing, I feel a negative pang when I think I’m making an obviously worse environmental choice in my purchases/lifestyle. It’s complicated, of course, but it’s fair to say that a person who reads a significant number of books is making the better environmental choice by doing so with a digital format. I’ve already done the same with music, disposing of my LPs and CDs years ago. Now I have access to virtually all of the world’s recorded music with virtually zero additional environmental impact. Same with books, obviously. We no longer have a stack of newspapers and other periodicals to toss in the recycling every week. The paper boy has long been out of business; for years the paper was delivered by a person driving through the neighborhood. Now there’s negligible carbon going into the atmosphere to get me my reading material.

I recently dug through the physical files I’ve kept of personal correspondence and my own writing. I have embarrassing stories and essays from high school and college, letters from family, ex-girlfriends, former students, colleagues, random certificates and other ephemera. One of my favorites is a poem written by my camp-counselor colleagues about the time I got super drunk with them after hours, while the kids were sleeping in their cabins.

I’ve always liked the term “ephemera” for random paper, as it conveys the feeling I have about all this now. I have my paternal grandfather’s union paybook from his time as a cook in New York, my father’s birth certificate with his correct middle name on it (he always went by a different middle name because he didn’t know what his official name was until he found the document late in life.) There’s a newspaper article about my maternal grandfather on his retirement as a mail carrier which was notable mostly because he described his daughter, my mother, as “pink” because of her left but not quite communist leanings. There are the letters he wrote to his bride while he was stationed in France during World War I.

For whatever reasons of history, travel and convenience, there is way more ephemera from my lifetime. There were moments when I thought it was a bit egotistical to keep all of this stuff in disorganized files in our one file cabinet, but I’m pretty sure I would have wanted more like this from my own parents, so I’ll leave it to the next generation to read what they want and decide what to do with it. Maybe they will digitize all of it.

There’s an equivalent amount of digital stuff, too, of course. Way more, actually, some of which is easily accessible with the right password. I have about four scrawled journals I’ve very sporadically kept, much of the writing from my classrooms when I responded to some question I asked the class to write about, like, “In what ways does the order of chapters at the end of Heart is a Lonely Hunter heighten the novel’s optimism or pessimism?” Otherwise it’s 95% digital.

Other material, especially email, is already falling off a digital cliff. My first email address was an aol, of course. Then mindspring, yahoo, now gmail. Plus work emails.

Will there be a way for the next generations to flip through their family’s digital ephemera? I assume the desire will still be there. Will the experience be the same?

I just finished reading The Weight of Ink by Rachel Kadish. Among other things, the book is about ephemera and its value, sometimes far beyond what it meant when it was created. Esther, one of the protagonists, asks that her writing be burned when she dies. It isn’t, and its discovery gives the novel its purpose. The papers are discovered hidden behind a staircase in a 15th century house. Is there a digital equivalent to that kind of discovery?

Letters from my mom while I was at college aren’t going to change history, but I can see my grandchildren being interested, one day, in what their great grandmother had to say to their grandpa when he was 18. Will it matter to my great granddaughter that she’s holding in her hands the piece of paper, with semi-legible handwriting, that was once touched by her great grandfather and great great grandmother? If someone digitizes it along the way will it one day be more accessible and more read? Or just another meaningless digital document that no one is interested in because it lacks that tangible sense of history?

Most of this kind of paper has been tossed at one time or another. Many families never had the chance to create it, even just two or three generations ago. Will great aunt Janey’s TickTok be accessible and interesting to her grandnieces and nephews, fifty years from now? Substack will be long forgotten by then, no doubt. Should I print this article out at the library and shove it in the files? Or maybe its ephemeral quality is more meaningful in some kind of human way, digital or hard copy.

Another interesting missive. I have switched almost exclusively to digital. I have also tried my best to hang on to a few letters, news articles and other “paper” memories. Continue to work on collecting family photos, both old and new.

I do miss the Sunday Travel Section of the NYT when we last had a paper subscription about 15 years ago. The only time I sit and read a newspaper (with coffee, of course) is when we visit MJ’s sister. Her husband reads the Wall Street Journal each morning, so I join him.

We have gotten rid of most of our books, but have kept some because of their value, bot sentimental and literary.

BTW….have been thinking more about contributing on this platform, but don’t seem to have the time….will have to work on that.

Cheers

I think what I love about a physical book is it's much easier to give to someone else. To share, and using the library feels like a civic good these days. For my own pleasure reading I switch between many forms. Audio book to physical to digital depending on travel, what my days look like etc. I like reading a physical book before bed, but I like having the digital on the go and the audio book for long drives or travel. I I feel like my own children absorb something growing up among some of the books that shaped me. But maybe it's all nostalgia.